Forest Legacy

The Forest Legacy Program is a cooperative partnership between USDA Forest Service (USFS) and Oklahoma Forestry Services. Authorized by Congress in 1990, the purpose of the Forest Legacy Program is to identify and protect environmentally important forestland from conversion to non-forest uses, through the use of conservation easements or fee purchase acquisitions negotiated with willing landowners.

Interested landowners are key in the development of the Forest Legacy Program. Landowners gain from the conveyance of their land interest and potentially benefit from reduced taxes. Participation in the program is voluntary and consists of two elements:

- Conveyance of interests in lands to achieve the land conservation objectives of the Forest Legacy Program; and

- Preparation of a Stewardship Management Plan or multi-resource management plan for protected sites. The management plan must be prepared and approved prior to signing the acquisition of the easement. Future modifications of the plan must be agreed to by the State lead agency. A plan is not needed if the landowner does not retain the right to harvest timber or conduct other land or resource management activities, or if the land is sold in fee.

Funding for Forest Legacy projects is sourced from the Land and Water Conservation Fund allocated by Congress. Funds are awarded through a nationwide, competitive process. 75% of project costs are covered by the federal government, and 25% are covered by state, private, and/or local sources.

Forest Legacy Program in Oklahoma

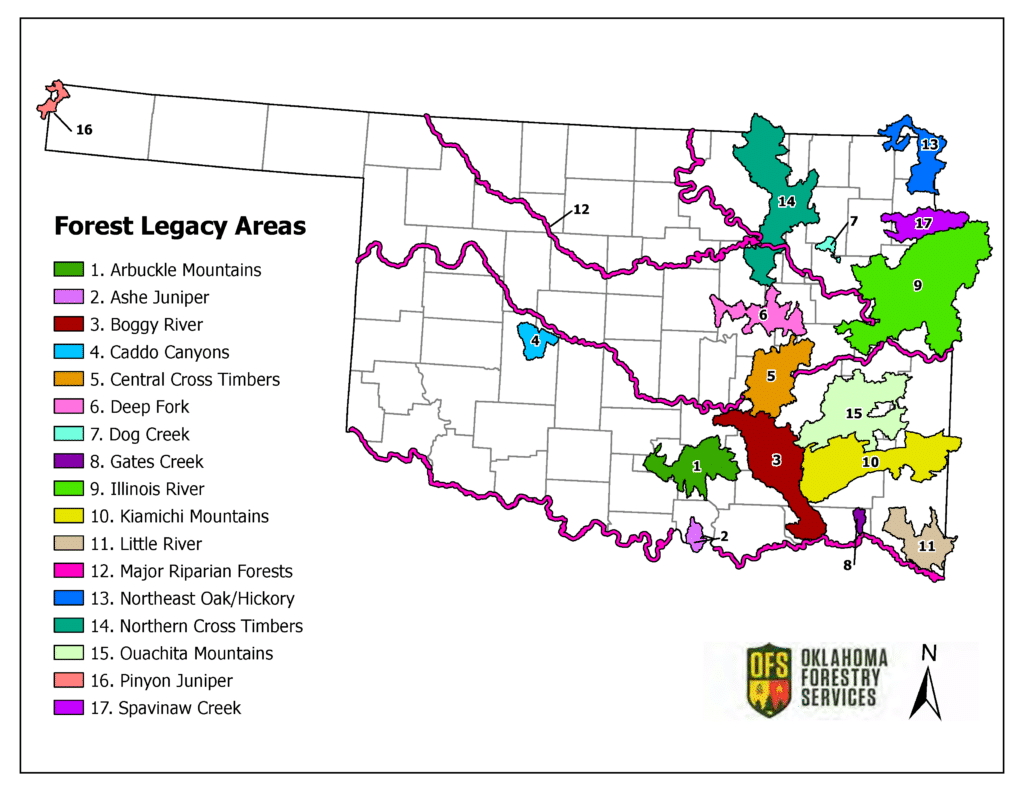

The wide diversity of Oklahoma’s landscape affords us vast tracts of forest land with unique features and special value to recognize and conserve, especially those that are being threatened by conversion to a non-forest use. In addition to various easement programs in place in the state, the federal Forest Legacy Program offers Oklahoma an opportunity to compete for funding to help maintain and conserve these special places. Oklahoma Forestry Services, with the help of the public and other agencies and organizations (including The Nature Conservancy and Oklahoma Department of Wildlife Conservation), has identified forested areas with unique features or special value that are being conserved for future generations. These areas are called Forest Legacy Areas and are shown on the map below. Only willing private landowners within these approved Forest Legacy Areas are eligible to work with Oklahoma Forestry Services to submit a Forest Legacy project application.

Click here to read/download Oklahoma’s Forest Action Plan.

Current Projects

Musket Mountain Forest

Oklahoma Forestry Services has managed and protected Oklahoma’s diverse forest resources since 1925 as part of the Oklahoma Department of Agriculture, Food, and Forestry. Today, 100 years after the division’s creation, Oklahoma Forestry Services (OFS) is partnering with The Conservation Fund to establish our first state forest in a renewed commitment to Oklahoma’s natural heritage.

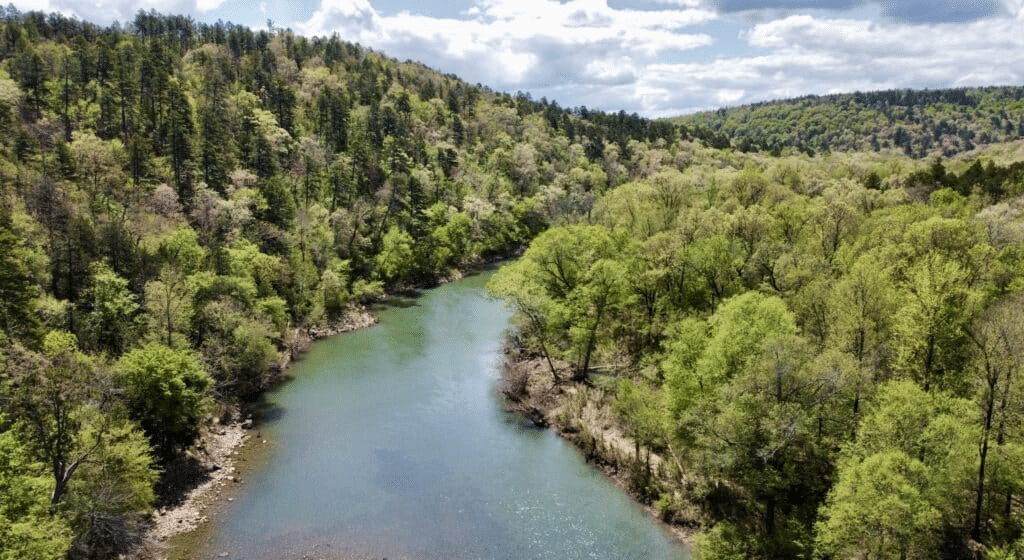

Nestled in the Ouachita Mountains of the Choctaw Nation in the heart of southeast Oklahoma’s woodbasket, the fee acquisition of the 11,333-acre Musket Mountain Forest is the opportunity of a lifetime for Oklahoma Forestry Services to establish what will tentatively be known as the Musket Mountain State Forest, Oklahoma’s first state forest. Surrounded by federal and state lands, including the 1.8 million-acre Ouachita National Forest, the Musket Mountain Forest has slopes and ridgelines comprised of mixed pine-oak forest and loblolly pine plantations, 41 miles of streams (including 2.6 miles of the Little River), and 51 miles of interior roads. These three key elements support Oklahoma Forestry Services’ vision to create a state forest legacy that will:

- support Oklahoma’s forest economy that generates $6.9 billion in annual revenue;

- strengthen their education and training capacity;

- protect critical wildlife habitat for three federally listed species and key game species;

- protect water quality in the Red River watershed; and

- secure permanent public access to support Oklahoma’s $4.3 billion outdoor recreation economy.

The Musket Mountain Forest project is receiving up to $15.9 million through the Forest Legacy Program, creating an opportunity to showcase public-private land conservation partnership on the grandest of scales. Learn more about this project from the award announcement here: Forest Legacy 2025 Funded Projects | US Forest Service

The Little River in the Musket Mountain Forest

Contact

If you’re interested in applying for a Forest Legacy project, donating to a current project, or want more information on the Forest Legacy Program, please contact the Forest Legacy Program Coordinator.

Madison Gore, Forest Legacy Program Coordinator

Oklahoma Department of Agriculture, Food and Forestry

Forestry Services

2800 N Lincoln Blvd

OKC, OK 73105

405.967.8296

madison.gore@ag.ok.gov